U.S. Probes Treasuries Niche That Investors Claim Is Rigged by Big Banks

U.S. officials investigating the $12.8 trillion market for U.S. Treasuries are zeroing in on a practice of trading the debt before it’s issued, said a person familiar with the matter -- spotlighting trades that several recent lawsuits allege are part of big banks’ efforts to rig Treasury markets.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. tipped the government’s avenue of inquiry in a recent regulatory filing. In a standard passage about areas under regulatory scrutiny, the bank’s Nov. 2 disclosure included a handful of words that hadn’t appeared the previous quarter: “offering,” “auction” and “when-issued trading.” It was a reference, the person said, to a fresh line of exploration in the government’s broader, months-old investigation into Treasuries trading.

That shows officials’ interest in one of the least transparent corners of the world’s largest debt market. When-issued securities act as placeholders for bills, notes or bonds before they’re auctioned. The instruments change hands over the counter, with lifespans of just days. There’s scant public information on trading volumes or the market’s biggest players.

The U.S. Justice Department’s fraud section asked last month about when-issued securities as part of broader requests for documents it sent to most or all of the 22 primary dealers in U.S. Treasuries, according to the person familiar with the matter, who requested not to be identified discussing the ongoing probe. The Securities and Exchange Commission is also investigating Treasuries trading, this person said. The SEC and Justice Department declined to comment.

Authorities haven’t accused any of the banks of wrongdoing, and their inquiries remain in early stages. Yet investors, in recent lawsuits, have already provided one potential road map for investigators.

Traders at global banks colluded to artificially inflate the price of instruments that allow them to sell U.S. debt before they own it, and then bought the debt at auctions for an artificially suppressed price, unfairly profiting at investors’ expense, according to several lawsuits filed against the banks beginning in July. The banks haven’t responded to those allegations in court.

There’s no indication that Goldman Sachs, while out front with its disclosure, is under specific government scrutiny. A spokesman for the bank declined to comment on the probe or suits. Several of the large primary dealers contacted for this article -- including JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc., Morgan Stanley, Barclays Plc and Deutsche Bank AG -- also declined to comment on the document requests or suits.

Representatives from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and New York’s Department of Financial Services -- who people familiar with the probes have also said are investigating Treasury trading -- declined to comment.

Debt-Market Fixture

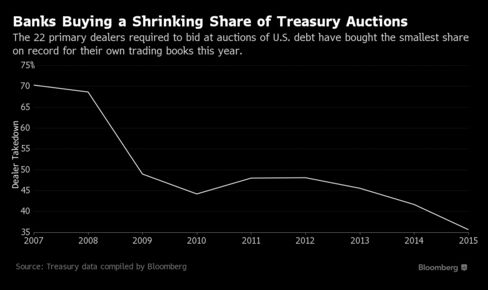

The probes and lawsuits come as many primary dealers’ bond-trading businesses have been squeezed by recent capital requirements from regulators, which have limited how much risk banks can take. This year, dealers’ purchases at Treasury note and bond auctions for their own trading books represent the smallest share on record, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

When-issued securities have been a government-debt market fixture since the U.S. Treasury Department effectively authorized their use in 1975. Investors can buy them from a Wall Street bond dealer to guarantee they will be able to get their hands on a bond, bill or note once it’s auctioned by the government.

Because they give a preview of auction demand, when-issued securities are an important indicator for primary dealers, which are essentially required to backstop U.S. government debt auctions by making “reasonable” bids for their share of each sale. The instruments help auctions run more efficiently, according to authorities including the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which supervises the primary dealers.

‘Tailing’ Auction

When prices move against dealers, trades in when-issued Treasuries can be unprofitable. On the other hand, a dealer that sells its customer a commitment to deliver U.S. debt at one price -- and then pays a lower price for that debt at auction -- can capture the difference when it delivers the Treasuries at the higher price it locked in.

When debt sells for less than when-issued prices indicate, traders say the auction "tailed." Auctions tailed more than half the time in every type of security except for the 10-year note between 2010 and 2014, a Cleveland pension fund alleged in a lawsuit against the 22 primary dealers filed Aug. 26 in Manhattan federal court. The chances that a supposedly predictive market would be so consistently off, in a direction that favors the people selling the security, is lower than 1 percent, the fund alleged.

Client Bids

The banks selling when-issued securities are often the same ones that receive billions of dollars worth of client bids for those same auctions. That raises the concern -- taken as a given in several of the recent suits -- that information is being shared within and between banks.

Trader-to-trader communication is at the heart of recent federal antitrust probes into whether banks coordinated to manipulate interbank interest rates and align foreign-exchange trades. Those cases have resulted in billions of dollars in penalties, and in some cases guilty pleas. The Treasury market investigation grew out those cases, people familiar with it have said.

Traders working at some primary dealers had the opportunity to learn about client auction bids ahead of time and in some cases talked online to counterparts at other banks, people familiar with these operations told Bloomberg News in June. That report is cited in several of the lawsuits alleging collusion related to when-issued securities.

‘Two-Pronged Scheme’

Traders at primary dealers used a “two-pronged scheme” to maximize the spread between their cost of selling the when-issueds and buying bonds at auction, a retirement fund for Boston’s public employees alleged in a July complaint filed in federal court in the Southern District of New York.

The traders “agreed to artificially inflate the prices of Treasury securities in the when-issued markets” by communicating to coordinate their trading, according to the complaint, which is based in part on an analysis of trading data. The traders coordinated their bidding strategies to artificially suppress the prices they would pay at Treasury auctions, the complaint alleged.

“Defendants were able to reap supracompetitive profits,” it added. The suit is now the lead among about two dozen similar actions that have been consolidated in federal courts in New York, Chicago and the Virgin Islands.

The “conspiracy ultimately collapsed” around December 2012, around the time the Justice Department secured a bank plea agreement from UBS Securities Japan Co. Ltd. related to manipulating interbank interest rates, according to the complaint. The UBS deal was among the first that the U.S. struck with banks in probes encompassing rate-fixing and collusion that have since cost banks billions of dollars in penalties globally.