China Exodus Money - Here's how the Chinese send billions abroad to buy homes

The ranks of China’s wealthy continue to surge. As their economy shows signs of weakness at home, they’re sending money overseas at unprecedented levels to seek safer investments — often in violation of currency controls meant to keep money inside China.

This flood of cash is being felt around the world, driving up real estate prices in Sydney, New York, Hong Kong and Vancouver. The Chinese spent almost $30 billion on U.S. homes in the year ending last March, making them the biggest foreign buyers of real estate. Their average purchase price: about $832,000. Same trend in Sydney, where Chinese investors snap up a quarter of new homes and are forecast to double their spending by the end of the decade. In Vancouver, the Chinese have helped real estate prices double in the past 10 years. In Hong Kong, housing prices are up 60 percent since 2010.

In total, UBS Group estimated that $324 billion moved out last year. While this year’s numbers aren’t yet in, during the three weeks in August after China devalued its currency, Goldman Sachs calculated that another $200 billion may have left.

So how do these volumes of cash get out when Chinese are limited by rules that allow them to convert only $50,000 per person a year?

The methods include China’s underground banks, transfers using Hong Kong money changers, carrying cash over borders and pooling the quotas of family and friends — a practice known as “smurfing.” The transfers exist in a gray area of cross-border legality: What’s perfectly legitimate in another country can contravene the law in China.

“It’s not legal for people to use secret channels to move money abroad, because this is smuggling,” says Xi Junyang, a finance professor at Shanghai University of Finance & Economics. “But the government has kept a laissez-faire attitude until recently.”

Now, policy makers are starting to take the outflow seriously. While it’s not about to run out of money, China has intensified a crackdown on underground banks that illegally channel cash abroad. It’s also trying to capture officials suspected of fleeing overseas with government funds.

Longer term, China has pledged to remove its currency controls and make the yuan fully convertible by 2020. Here are some common methods millions of Chinese are using to get a head start:

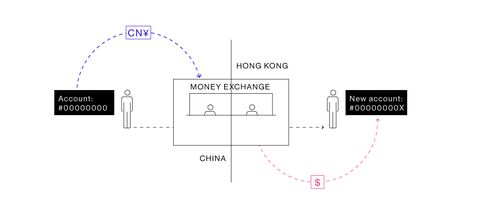

1. Go to a Hong Kong Money Changer

Daniel Zhang, 34, is a self-made millionaire who lives in China’s southern city of Shenzhen. Earlier this year he gave the equivalent of $77,000 to a local money-changing shop and saw it appear less than an hour later in a bank account he had previously opened across the border in Hong Kong.

“It was easier than I expected and cost little,” says Zhang, who bought Hong Kong stocks with the money. “I don’t know whether this is legal, and I don’t care that much.”

In Hong Kong, more than 1,200 currency-exchange shops have seemingly little daily activity. These brightly lit storefronts specialize in helping wealthy Chinese transfer their money overseas. The premium isn’t high — only about 1,000 yuan ($160) per HK$1 million ($130,000) more than bank exchange rates would be if they could do the transaction.

It works like this: Chinese come to Hong Kong and open a bank account. Then they go to a money-change shop, which provides a mainland bank account number for the customer to make a domestic transfer from his or her account inside China. As soon as that transaction is confirmed, typically in just two hours, the Hong Kong money changer then transfers the equivalent in Hong Kong or U.S. dollars or any other foreign currency into the client’s Hong Kong account. Technically, no money crosses the border -- both transactions are completed by domestic transfers.

While the first exchange has to be set up face-to-face, customers can place future orders via instant-messaging services such as WhatsApp or WeChat, and money changers set no limit on how much money they can move. If the shops need to top up reserves in say, Hong Kong, they can transfer money directly from the mainland as a business transaction, which isn’t subject to the same currency controls as individuals.

“We have customers who took out HK$8 million and planned to use the money to make investments or buy properties,” says a manager at a money-change shop in Hong Kong’s Mongkok district, who only gave her surname as Wong. “I think it’s legal as long as customers provide enough documents.”

Wong’s shop makes about HK$4,000 in profit from each HK$1 million transaction.

Hong Kong banks have been stepping up controls to report suspicious transactions and reduce the risk of financial crime, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority said in response to questions, noting that banks accounted for 83 percent of reports last year to the police-customs agency that helps investigate money laundering.

“Hong Kong is a gateway” for the Chinese to move cash to other countries, says David Ji, Hong Kong-based head of research for greater China at real estate brokerage Knight Frank LLP. “Once the money arrives in Hong Kong, it’s free as a bird.”

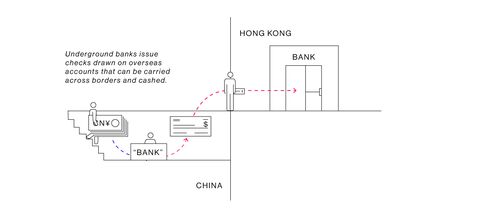

2. Carry a Check From an Underground Bank

Even with a $500,000 U.S. dollar check in his pocket, 10 times the amount allowed by law, factory owner Frank Deng felt at ease as he passed though Chinese customs from Shenzhen to Hong Kong earlier this year.

He got the check from a so-called underground bank in southern China’s Guangdong province, drawn from a Hong Kong bank account and denominated in U.S. dollars so that it could be cashed upon crossing the border. Deng had given the “bank,” which operates as part of China’s shadow-banking system, the equivalent in yuan from his account in China in order to receive the check. Using that money, plus other deposits on other trips, Deng planned to make a 50 percent down payment on a HK$10 million apartment.

“I normally do large-amount foreign currency conversions through underground banks due to the capital controls,” says Deng. “I took checks only because that’s easy for me or my friends to carry abroad and can help avoid scrutiny from customs.”

Residential prices in Hong Kong rose 13.5 percent last year and have gained another 9.5 percent this year to reach a record.

“Without informal channels,” says Ji of Knight Frank, “how could you possibly explain the surge in Hong Kong property prices?”

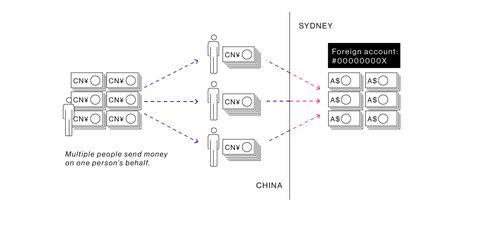

3. Recruit ‘Smurfs’ to Pool the Quota

Jenny Cai, a Shanghai resident, bought a A$1.2 million ($867,000) apartment in downtown Sydney after seeing pictures at a marketing event in Shanghai. To do it, she asked her husband and daughter to combine their $50,000 annual quotas with hers to come up with the down payment.

The practice is called “smurfing” - named after the little blue cartoon characters who collectively make up the whole. Also known in Chinese as “ants moving their house,” for small grains of dirt being moved individually, the government has started restricting the amounts of cash that can be moved in this way, as well as how often banks can send money to a single account abroad from multiple sources.

Cai intends to pay the mortgage by renting out the place, as well as pooling her family’s quotas in coming years.

“The purchase is the easy part,” says Cai, 37, who works for an export company. “Making payments is a lot of hassle.”

She regrets not taking up what her property agent called a “secret channel” to get her money to Sydney, she said. “The fee they charge for that is worthwhile in retrospect.”

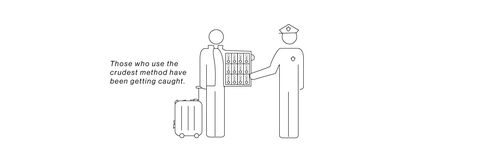

4. Carry Cash in Your Suitcase

Mainland Chinese make news by being caught with cash in their luggage or strapped to their bodies: Shenzhen customs stopped 80 people trying to smuggle a total of 30 million yuan into Hong Kong in the first three months of this year, Ming Pao newspaper reported. In Vancouver and Toronto, customs agents seized $15,019,891 in cash or checks from 869 Chinese nationals from June 2012 to December 2014, according to Canada’s National Post.

China caps the amount of cash that tourists can take abroad to 20,000 yuan in local currency and the equivalent of $5,000 in foreign currencies.

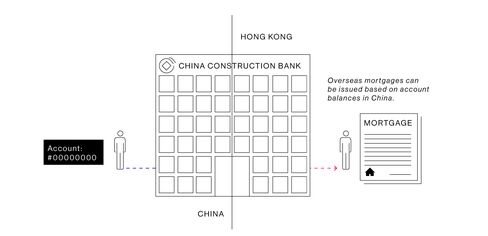

5. Get an Overseas Mortgage Based on Your China Savings

For the most affluent people, Chinese banks offer a legitimate channel to get money for home purchases overseas. China Construction Bank Corp., the nation’s second-largest lender, last year started a product that enables its private banking clients to borrow up to HK$20 million in Hong Kong by using yuan-denominated deposits and other assets on the mainland as collateral, according to an advertisement. China Construction Bank spokesmen declined to comment on the offer.

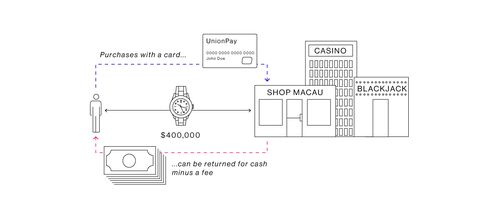

6. Pay by Credit or Debit Card, Then Return the Merchandise for Cash

A Chinese tourist using a UnionPay credit or debit card overseas can “buy” an item such as an expensive watch that is further marked up, from a merchant who allows the item to be immediately returned. Instead of refunding the purchase price back to the card, the store reimburses the customer in cash, typically taking a fee of 5 percent to 10 percent for the cashback service.

The practice came to light in pawn shops surrounding the casinos of Macau -- giving the Chinese “purchasers” instant cash for gambling or to spirit abroad. A government crackdown has curbed cashback services in the gambling enclave, but it has since been reported elsewhere. A UnionPay press officer in Shanghai said the company had no comment on the practice.

Using another method, over-invoicing, a business owner in China can get cash abroad by agreeing to pay a mark-up for an item sold outside of China. After a separate agreement is made with the vendor on the real price, the inflated amount is transferred from China legally for the purchase, and the vendor refunds the difference to the purchaser into an account outside of China.