Induction to Multi-National Sanctions Programs and Evasions Tactics

8th November 2018, Bachir El Nakib (CAMS), Senior Consultant, Compliance Alert LLC (Qatar- Lebanon)

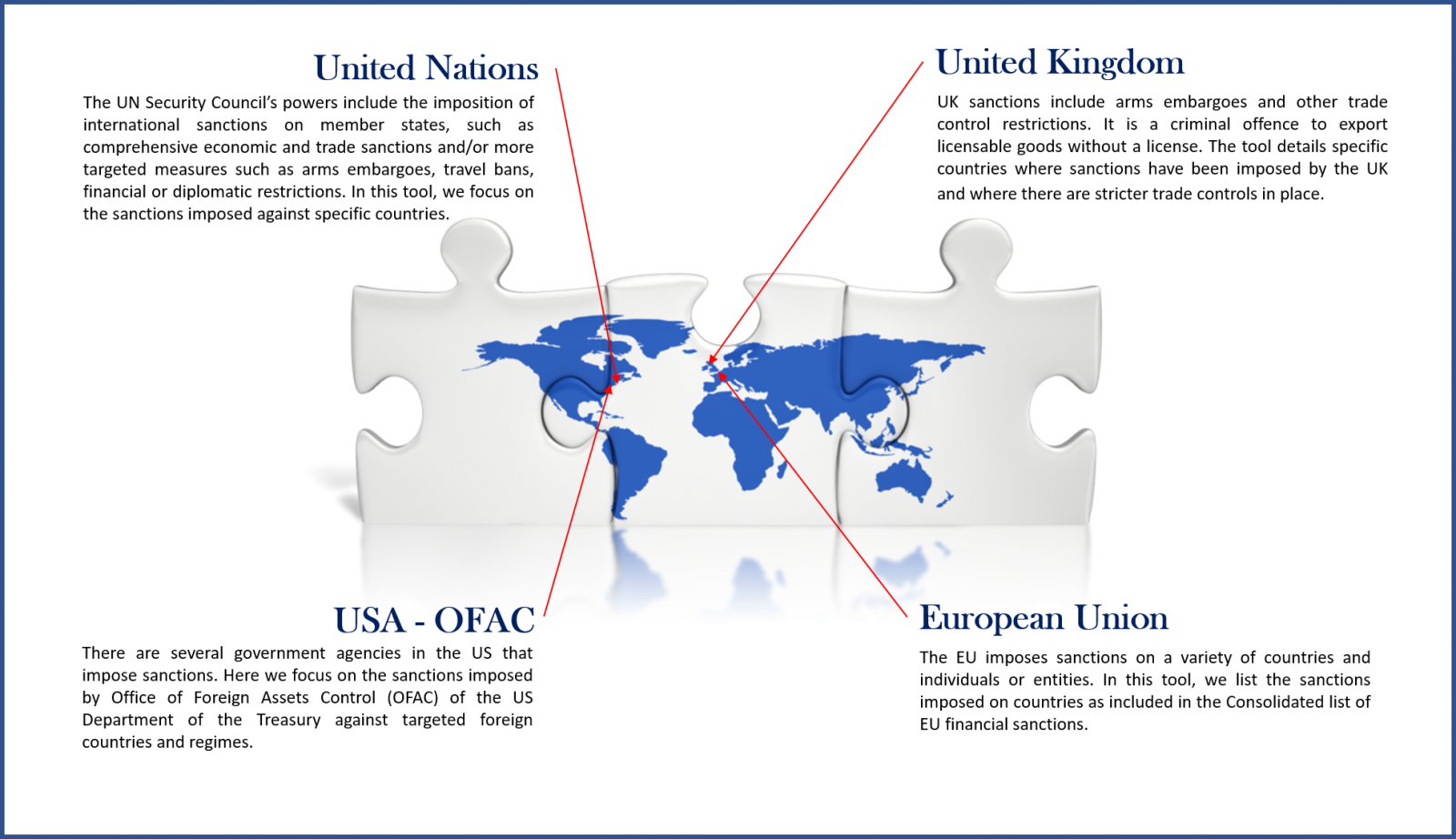

Following our recent article: Induction to OFAC Economic Sanctions Program, what's the purpose of sanctions in different multinational jurisdictions.

The purpose of sanctions

Sanctions are a tool of foreign policy, and aim “to coerce a change in behaviour, to constrain behaviour, or to communicate a clear political message to other countries or persons”. The EU describes them as: “an essential tool of the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy … used by the EU as part of an integrated and comprehensive policy approach, involving political dialogue, complementary efforts and the use of other instruments at its disposal”.

Dr Erica Moret, Senior Researcher and Chair of the Geneva International Sanctions Network, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, described sanctions as a “useful middle ground between war and words”; they are “a policy instrument that can put pressure on targeted entities short of military action”.

“Sanctions have become a central tool of national security”, according to Mr David Mortlock, Partner, Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP, and Mr Richard Nephew, Adjunct Professor and Senior Research Scholar, Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia University. While acknowledging that questions are often raised about the effectiveness of sanctions, Mr Ross Denton, Partner, Baker and McKenzie LLP, told us that “in certain industries they are very effective”. For example:

“They have changed the nature of business in Russia, they have changed the way in which certain businesses operate, and they have changed the way in which Russia wants to do business with the West.”

The different types of sanctions—arms embargoes; asset freezes; visa or travel bans; and other sectoral restrictions—are described in Box 1 below: Types of sanctions

|

Arms embargoes Arms embargoes normally cover the sale, supply and transport of military goods. In EU regimes, these must be included in the EU’s Common Military List.8 Related technical and financial assistance is usually also included in the ban. The export of equipment used for internal repression, and dual-use goods (that can be used for both civil and military purposes) may also be prohibited. Asset freezes Asset freezes concern funds and economic resources owned or controlled by targeted individuals or companies. Funds, such as cash, cheques, bank deposits, stocks and shares may not be accessed, moved or sold, and other tangible or intangible assets—including real estate—cannot be sold or rented. Asset freezes also include a ban on providing resources to targeted individuals or companies. In effect, business transactions with targeted individuals or companies cannot be carried out. Visa or travel bans Individuals targeted by a travel ban are denied entry to the sanctioning country at its external borders. If visas are required for entering the country, they will not be granted to people subject to such restrictions on admission. EU measures do not oblige an EU Member State to refuse entry to its own nationals. Other sectoral restrictions Sectoral restrictions include, for example, prohibitions on certain kinds of financial transactions or certain types of trade. |

Source: European Union Committee, The legality of EU sanctions (11th Report, Session 2016–17, HL Paper 102) and Q 1 (Maya Lester)

EU sanctions regimes include asset freezes, travel restrictions, arms embargoes and can also include broader sectoral restrictions (as set out in Box 1). EU sanctions apply: “within the jurisdiction (territory) of the EU; to EU nationals in any location; to companies and organisations incorporated under the law of a Member State—including branches of EU companies in third countries; on board of aircrafts or vessels under Member States’ jurisdiction”

The most effective sanctions regimes are designed and applied alongside international partners, to strengthen the signal to the target and deliver the maximum possible economic impact.

The EU’s sanctions regimes have a significant impact where agreement cannot be reached at the UN, or agreed UN measures are limited in scope. This reflects the significance of the EU as an economic bloc, and the signalling power of 28 Member States acting in concert.

Financial sanctions can be particularly effective in applying pressure to targeted entities. The role of the City of London as an international financial centre heightens the value of participation by the UK in collective sanctions regimes, at both UN and EU level

Types of USA Sanctions

US sanctions or embargoes take various forms. Some may be diplomatic in nature, such as removal of embassies, travel bans, or refusal to participate in an international sports or business event. Economic sanctions include asset freezing, arms embargoes, foreign aid reduction and trade restrictions such as defense articles, including weapons systems, components, training or services.

Economic sanctions may prohibit commercial activity with a country, like the now-softening US embargo of Cuba, or they may be targeted, such as to block transactions with specific businesses or individuals, like the sanctions against members of Al Qaeda. The Departments of State, Commerce, and Treasury produce lists of debarred, denied, or prohibited parties. Unless one has a specific license from these departments, trade with these parties is not allowed.

How US sanctions are implemented

Economic sanctions are imposed either under a law or by Executive Order (EO) of the President, who is acting under the power extended by law.

Sanctions that originate with a law include the International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA), which authorizes the President to declare a national emergency in response to an extraordinary foreign threat to the US. The IEEPA empowers agencies, such as the Commerce Department’s Export Administration Regulations (EAR), to promulgate implementing regulations. The President has broad powers to implement, change or remove sanctions under IEEPA if Congress does not restrict them.

How are US sanctions enforced?

Several US federal agencies enforce sanctions. The agency that regulates a particular transaction depends largely on the type of activity or item that the sanctions program prohibits. Often, one transaction may be subject to regulatory action by more than one agency that jointly investigates the matter, thus exposing a business to possible investigations by multiple agencies.

Each agency issues a different “Do Not Touch” list, which identifies either whole countries (comprehensive) or individual companies or persons against whom the sanction is applied. As is the case with transactions, the organizations and individuals on these lists may overlap and the penalties imposed by sanctions agencies may vary widely depending on the applicable statute and purpose of the sanction.

OFAC, BIS and DDTC

Among the many US government agencies that play a role in sanctions enforcement, three play a pivotal role.

The Department of State’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) monitors and regulates export of defense trade. It administers the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). The ITAR is the US Munitions List, a comprehensive list of all defense articles and services that are subject to ITAR and control by DDTC. These articles include hardware items, software and technology, and services for use in a military setting, as well as certain space-related items and technology. The Arms Export Control Act is the enabling legislation for ITAR and also governs US trade in military items.

The Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) enforces the export controls applicable to so-called “dual-use” items and less sensitive military items. The BIS derives its power from the Export Administration Regulations (EAR). BIS primarily regulates items designed for commercial purposes, such as computers or software, including hardware and technology, which could have military applications. BIS keeps a list of regulated items called the Commercial Control List (CCL). BIS also regulates civilian items, not identified on the CCL, called “EAR99” items.

The Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) arguably plays the most important role in administering and enforcing US sanctions programs. The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which was enacted October 28, 1977, is the primary source of OFAC’s powers. IEEPA makes it a crime to willfully violate, or attempt to violate, any regulation under IEEPA, and institutions facing criminal enforcement action by the Department of Justice. OFAC publishes a list of lists of ‘Specially Designated Nationals’ (SDNs), which indicates individuals and companies to which sanctions and restrictions apply.

It is important to note that OFAC has a wide investigative mandate. Both BIS “dual use” items under the EAR as well as items falling under the ITAR subject to action by the DDTC involving sanctioned countries or persons may fall under the OFAC regulations.

Recent USA Sanctions settlements

In other recent sanctions cases:

-- U.S. federal and state authorities informed Standard Chartered Bank that they are preparing to bring criminal charges against two of the bank's former employees over alleged sanction breaches involving Iran-linked companies, the Financial Times reported.

The report said prosecutors were also seeking to fine Standard Chartered about $1.5 billion in a probe based on allegations the bank continued to breach such Iran sanctions by processing U.S. dollar transactions -- even after it paid a $667 fine in a 2012 settlement for such violations.

Standard Chartered PLC chief executive Bill Winters told senior staff on Tuesday that the bank is working on an "acceptable resolution" with these authorities. He said most of the transactions in question date to before 2012.

As part of it 2012 deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) with the U.S. Treasury, the bank said it had stopped working with Iranian and Iranian-connected companies, the FT said. StanChart closed its Tehran office in May 2012, the newspaper said.

The bank was subject to an independent monitor appointed to oversee its effort to improve its sanctions compliance program under its DPA; that agreement has already been extended twice, as the monitor has found supposed remedial efforts inadequate.

-- U.S. authorities last year alleged in civil and criminal charges that Chinese handset maker ZTE illegally shipped telecommunications equipment to Iran and North Korea. ZTE was also charged with obstruction for making false statements to the US. Commerce Department and destroying export records.

ZTE paid $1.19 billion in penalties to settle the 2017 case and promised to fire four senior employees and discipline 35 others by reducing their bonuses or reprimanding them.

In April, the Commerce Department said ZTE had not disciplined the 35 employees. Instead it "paid full bonuses to employees that had engaged in illegal conduct, and failed to issue letters of reprimand."

The United States then revoked the business' export privileges so ZTE was unable to get the parts manufactured in the United States that it needed to make its handsets. That caused the business to end its operations.

In exchange for reinstating U.S. exports, ZTE paid a $1 billion fine, reconstituted its board and accepted a U.S.-appointed compliance department. ZTE also paid an additional $400 million that it would receive back if it honors its promises.

-- In June, OFAC announced a $145,893 settlement agreement with telecommunications firm Ericsson to settle its potential civil liability for an apparent violation of OFAC's Sudanese sanctions regulations.

The violation involved employees of Ericsson units conspiring together and with employees of a third company to export and reexport a satellite hub from the United States to Sudan and to export and reexport satellite-related services from the United States to Sudan.

OFAC determined that the businesses voluntarily self-disclosed the apparent violation. But it also termed the violation egregious , because the employees conspired specifically to evade a U.S. embargo on Sudan, they ignored repeated warnings from the Ericsson's compliance department, and at least one employee was a manager.

-- HSBC Holdings Plc in 2012 paid a $1.9 billion settlement for helping Mexican drug cartels launder money and for breaching international sanctions by doing business with Iran.

HSBC agreed to cooperate with the U.S. Justice Department in return for not losing access to some of its most lucrative institutional banking activities in the United States.

The bank was also put under the supervision of an external monitor, Michael Cherkasky, who said in a report early in his monitorship that there had been resistance from senior managers at the investment bank.

HSBC purchased new technology and significantly increased its compliance team worldwide. The deferred prosecution agreement it signed with the Justice Department ended in December 2017, signaling the department's satisfaction with the bank’s compliance enhancements.

Beneficial ownership: Sanctioned entities will camouflage the beneficial ownership of the corporate vehicles they control to disguise their transactions. False identities, nominee directors or "straw men" (those who receive compensation for pretending to be the true owners) will be listed on the paperwork. Corporate ownership will daisy-chain throughout offshore financial havens renowned for their bank secrecy laws.

Offshore financial havens: Jurisdictions where off-the-shelf incorporation is a booming business will see increased interest in their services. Other jurisdictions suffering from conflict or political upheaval may find their corporate registries polluted with shady companies intent on evading inspection by American authorities. Such havens have traditionally been found in tropical environments, but are becoming more prevalent in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

The usual suspects of Switzerland and Grand Cayman are now passé, used primarily by amateurs. Laundering professionals have moved on to opaque locations that are normally off the radar. As China and Russia create numerous challenges for financial investigators, their use as offshore financial havens will only increase.

Corporate nesting: Sanctioned entities will "nest" their transactions within a company that is not named in sanctions lists. Companies willing to earn extra income by ingesting these transactions will run certain risks, yet they will be generously rewarded.

Institutional nesting: There are seemingly endless possibilities for dark correspondent banks willing to risk classification of "primary money laundering concern" by Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act. For financial institutions willing to run afoul of American sanctions policy set by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), massive fees can be earned by dealing with sanctioned banks, individuals, and companies. For example: Internal procedures can be adjusted to bypass sanctions lists; SWIFT messages can be stripped of sanctioned entity names; OFAC filters can be turned off; training programs can instruct bank staff on how to circumvent sanctions; and transactions can be routed through numerous unrelated jurisdictions.

National nesting: Not all countries agree with American sanctions policy. Those who adopt a more lenient approach to Iran will find themselves conduits for money launderers camouflaging Iranian banking activity. In the past, this list has included modern offshore financial havens. Now others are entering the fray, either by supporting their nationals who hold existing investments in Iran or who simply do not wish to abide by Washington's current rules.

Black market currency exchanges: The Black Market Peso Exchange (BMPE) was created in the 1970s to exchange Colombian pesos for USD, as a result of narcotics traffickers selling cocaine in Florida. The BMPE is an exchange of title for currency managed by brokers. The same scenario can exchange title of USD earned through oil sales for Iranian riyals or for USD to purchase imported goods into Iran.

Alternative currencies: Chinese currency (RMB) is now available to corporations in major financial centres around the world. The Hong Kong Dollar (HKD) has been pegged to the USD for decades and maintained its strength through several significant financial crises. Both currencies count on massive USD reserves to support their power within foreign exchange markets. Lately, Euro payments have found a more eager audience for those unwilling to have their payment details routed through a U.S. correspondent bank. Lower volume currencies – such as those from Switzerland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand – offer a degree of sanctuary, but their clearing banks will be closely following OFAC instructions, as they are heavily invested in the American banking industry and depend on USD access.

Cryptocurrencies may offer unique camouflage options, but they are thinly traded and relatively unfamiliar to the traditional players offering sanctions evasion services. Given the breadth of cryptocurrency product offerings, however, there may be unique solutions that solve traditional problems of transactional camouflage.

Professionalised laundering and evasion

Economic sanctions are the munitions of financial warfare. As they grow in magnitude, so do the responses by professional money launderers and dark financial institutions intent on profiting from their violation.

History has shown that some financial institutions will adopt a radically different approach from their peers by offering financial services to sanctioned entities and/or their counterparties to generate exceptional profits. Businesses operated by international banks that are classified as high-risk for money laundering – correspondent banking, trade finance, private banking, and capital markets – can be used to camouflage sanctions evasion activity within their gargantuan daily transactional volumes. Individuals and firms intent on offering sanctioned persons or entities access to global banking markets will exploit weaknesses within these four high-risk lines of business.

Iran poses unique challenge

The U.S. imposition of economic sanctions on highly isolated states, such as North Korea, is a fairly straightforward affair. Policy is dictated by Washington, and rules flow through the compliance departments of international financial institutions. Financial intelligence then flows into FinCEN and law enforcement, followed by action from various intelligence agencies acting on that information. Those who maintain banking and trade relations with North Korea face exclusion from a global financial system that remains reliant on U.S. dollar payments to power international trade, remittances, and capital markets.

In the case of Iran, however, complex geopolitical factors create a far more challenging enforcement scenario.

Since the United States relaxed economic sanctions in 2015, European countries have invested heavily in Iran's oil industry. With the looming re-imposition of sanctions, European firms now face writing off their investments or risking prosecution by American authorities for engaging with the Iranian economy.

Immediately following the August 6th White House sanctions announcement, the European Union (EU), United Kingdom (UK), France, and Germany released a joint statement on updating the EU's Blocking Statute, which "protects EU companies doing legitimate business with Iran from the impact of U.S. extra-territorial sanctions".

Although the Blocking Statute does not negate the risk of prosecution by American authorities for doing business with Iran, it certainly complicates those efforts.

Additionally, U.S. rivals Russia and China both require Iranian oil to fuel their growing economies. Given their mutual disdain for current U.S. foreign policy, their appetite for adhering to economic sanctions against Iran is limited.

As such, those using money laundering techniques to evade sanctions may find that many financial centres are less enthusiastic about enforcing U.S. policies.

Evasion Tactics

A common set of sanctions evasion techniques and themes emerged during the last round of sanctions, and they will feature even more prominently in the next round. They are as follows:

he State Department, Treasury Department and Homeland Security have issud an advisory highlighting the sanctions evasion tactics used by North Korea that could expose companies—including manufacturers, buyers, and service providers—to compliance risks under U.S. or United Nations sanctions authorities.

This advisory is also intended to assist businesses in complying with the requirements under Title III, the Korean Interdiction and Modernization of Sanctions Act of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA).

This advisory does not impose new sanctions on North Korea. The U.S. remains committed to the Joint Statement that President Trump and Chairman Kim signed June 12 in Singapore. As the President has said, sanctions will be enforced and remain in effect.

Multiple U.S. and UN sanctions impose restrictions on trade with North Korea and the use of North Korean labor, potentially impacting a company’s supply chain operations. The two primary sanctions compliance risks are: inadvertent sourcing of goods, services, or technology from North Korea, and the presence of North Korean citizens or nationals in those supply chains, whose labor generates revenue for that government.

Concerning the inadvertent sourcing of goods, services, or technology from North Korea, companies are advsed to be aware certain practices:

- Sub-Contracting/Consignment Firms: Third-country suppliers shift manufacturing or sub-contracting work to a North Korean factory without informing the customer or other relevant parties. For example, a Chinese factory sub-contracts with a North Korean firm to provide embroidery detailing on an order of garments.

- Mislabeled Good/Services/Technology: North Korean exporters may disguise the origin of goods produced in the country by affixing country-of-origin labels that identify a third country. For example, North Korean seafood is smuggled into third countries where it is processed, packaged, and sold without being identified as originating from North Korea. There are also cases in which garments manufactured in North Korea are affixed with "Made in China" labels.

- Joint Ventures: North Korean firms have established hundreds of joint ventures with partners from China and other countries in various industries, such as apparel, construction, small electronics, hospitality, minerals, precious metals, seafood, and textiles.

- Raw Materials or Goods Provided with Artificially Low Prices: North Korean exporters sell goods and raw materials well below market prices to intermediaries and other traders, which provides a commercial incentive for the purchase of North Korean goods. This practice has been documented in the export of minerals. For example, a close review of trade data on North Korea’s export of anthracite coal to China from 2014-2017 reveals a consistent sub-market price for this export.

- Information Technology (IT) Services: North Korea sells a range of IT services and products abroad, including website and app development, security software, and biometric identification software that have military and law enforcement applications. North Korean firms disguise their footprint through a variety of tactics including the use of front companies, aliases, and third country nationals who act as facilitators. For example, there are cases where North Korean companies exploit the anonymity provided by freelancing websites to sell their IT services to unwitting buyers.

Regarding North Korea's overseas labor, the advisory warns that “the North Korean government exports large numbers of laborers to fulfill a single contract in various industries, including but not limited to apparel, construction, footwear manufacturing, hospitality, IT services, logging, medical, pharmaceuticals, restaurant, seafood processing, textiles, and shipbuilding.

The advisory also lists 41 countries and jurisdictions where North Korean laborers were found working on behalf of the North Korean government. “China and Russia continue to host more North Korean laborers than all other countries and jurisdictions combined,” it says.

The government warns companies to “be aware of these deceptive practices in order to implement effective due diligence policies, procedures, and internal controls to ensure compliance with applicable legal requirements across their entire supply chain.

http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-4805_en.htm

https://www.reuters.com/

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/hsbc-holdings-plc-and-hsbc-bank-usa-na-admit-anti-money-laundering-and-sanctions-violations

https://www.complianceweek.com/blogs/the-filing-cabinet/advisory-warns-companies-about-sanctions-evasion-tactics-used-by-north#.W_Ep34czbIU