The Russian Laundromat Exposed in Full

23 March 2017

Reviewed-Edited, by Bachir El Nakib, Senior Consultant, Compliance Alert (LLC)

Britain is struggling to stop vast sums of potentially criminal money entering the country because investigators are being hampered by the Russian authorities, the head of the National Crime Agency money laundering unit has said.

In an interview with the Guardian, David Little said: “The amount of Russian money coming into the UK is a concern. “One, because of the volume. Two, we don’t know where it is coming from. We don’t have enough cooperation [from the Russian side] to establish that. They won’t tell us whether it comes from the proceeds of crime.”

Labour has been granted an urgent question in the Commons on the subject. The shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, will raise the issue at 12.30pm on Tuesday in a debate, with a government minister responding.

Little, who is head of the NCA’s money laundering and corruption intelligence desk, said his team exchanged information with the Russian Financial Investigation Unit.

But he hinted that frosty diplomatic relations between the UK and Moscow, and the murky internal politics of Russia itself, made it impossible to pursue leads.

He pointed to the “wider relationship issues that exist within Russia”, adding: “Overall, the [UK-Russia relationship], it’s very challenging.”

On Monday, the Guardian revealed that police in eastern Europe have been investigating how at least $20bn was moved out of Russia during a four-year period from 2010. Detectives have exposed a money laundering scheme, called the “Global Laundromat”, that was run by Russian criminals with links to their government and the former KGB.

Documents seen by the Guardian show British-registered firms played a prominent role in the money laundering network – and the UK’s high street banks processed $740m from the operation without turning back any of the payments. The banking records were obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and Novaya Gazeta from sources who wish to remain anonymous. OCCRP shared the data with the Guardian and media partners in 32 countries. The documents include details of around 70,000 banking transactions, including 1,920 that took place in the UK and 373 in the US.

The data is understood to be part of the evidence gathered in a money laundering investigation led by police in Moldova and Latvia that has been running for three years.

Little said the NCA had been in touch with the authorities in Moldova since 2014 about the Global Laundromat, which he described as “big and pretty unusual”.

He acknowledged that UK banks had taken steps to identify laundered money, but insisted they needed to spend more on compliance, even though it “isn’t the part of the bank that makes money”.

“I think the [banks] have significant challenges. Twenty million transactions go through the City and in trades through the money markets each day. A vast amount of business, and only a small amount will be money laundering.

“It’s the size of the challenge which is the problem. It’s beyond a human scale. The sophisticated money launderer will know the tolerances that will trigger alerts. There are pretty smart guys out there. This needs more sophisticated solutions than throwing people at it. It’s not just about the size of the staff.

“[The banks] are improving but they can still get better.”

Little said he thought it was likely that other sophisticated, long-running schemes like the Laundromat were still being used by criminals.

“Typically these schemes operate for a number of years. The money moves through it. It keeps churning away until something triggers it [to stop]. These are the most dangerous schemes.”

He said the NCA would be reviewing its work on the Laundromat in the light of the revelations.

“We have an interest in all money laundering schemes like this, particularly where UK structures appear to have facilitated it.”

Robert Barrington, the executive director of Transparency International UK, said the revelations of the UK’s role in financial crime should “come as no surprise to anyone”.

“A year after the Panama Papers, we can see that the anti-money laundering supervisors have been asleep on the job, the banks have been at best lax and at worst complicit, and the UK’s law enforcement agencies have a dismal track record of investigations that lead to prosecutions.

“Basically, the UK’s anti-money laundering defences are just not fit for purpose. The government needs a concerted, world-class strategy to deal with this if it’s going to convince people that we are not in a post-Brexit race to the bottom in which corrupt money is welcomed to the UK with open arms.”

Barrington said it was good that that criminal finances bill was currently before parliament, but added: “The bad news is that at last year’s anti-corruption summit, the government promised to publish a national anti-corruption strategy by December, and there is no sign of it.”

Roman Borisovich, a former banker and anti-corruption campaigner, said the British government needed to do more to end offshore secrecy. It should identify the real owners of offshore companies doing business or owning assets in the UK.

“In Russia I have witnessed an entire shadow industry of money laundering engineered by professional financiers and operated by organised criminal groups under the Kremlin’s watchful eye,” he said.

According to the Central Bank of Russia, capital flight out of Russia during the Vladimir Putin years exceeded $1tn, he said. “We have no idea yet how the other $900m got across the Russian border – but rest assured they ended up in the same banks.”

HSBC, the Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds, Barclays and Coutts are among 17 banks based in the UK, or with branches here, that are facing questions over what they knew about the international scheme and why they did not turn away suspicious money transfers.

HSBC processed $545.3m in Laundromat cash, mostly routed through its Hong Kong branch. The troubled RBS, which is 71% owned by the UK government, handled $113.1m. Coutts, which is owned by RBS and used by the Queen, accepted $32.7m of payments via its office in Zurich, Switzerland.

Coutts is winding down its Swiss operation and was last month fined by regulators for money laundering in a different case.

RBS said in a statement that also covered Coutts and NatWest: “We are committed to combating financial crime and money laundering in line with our regulations and have controls and safeguards in place to identify, assess, monitor and mitigate these risks.”

HSBC said: “This case highlights the need for greater information sharing between the public and private sectors, each of whom holds important information the other does not.”

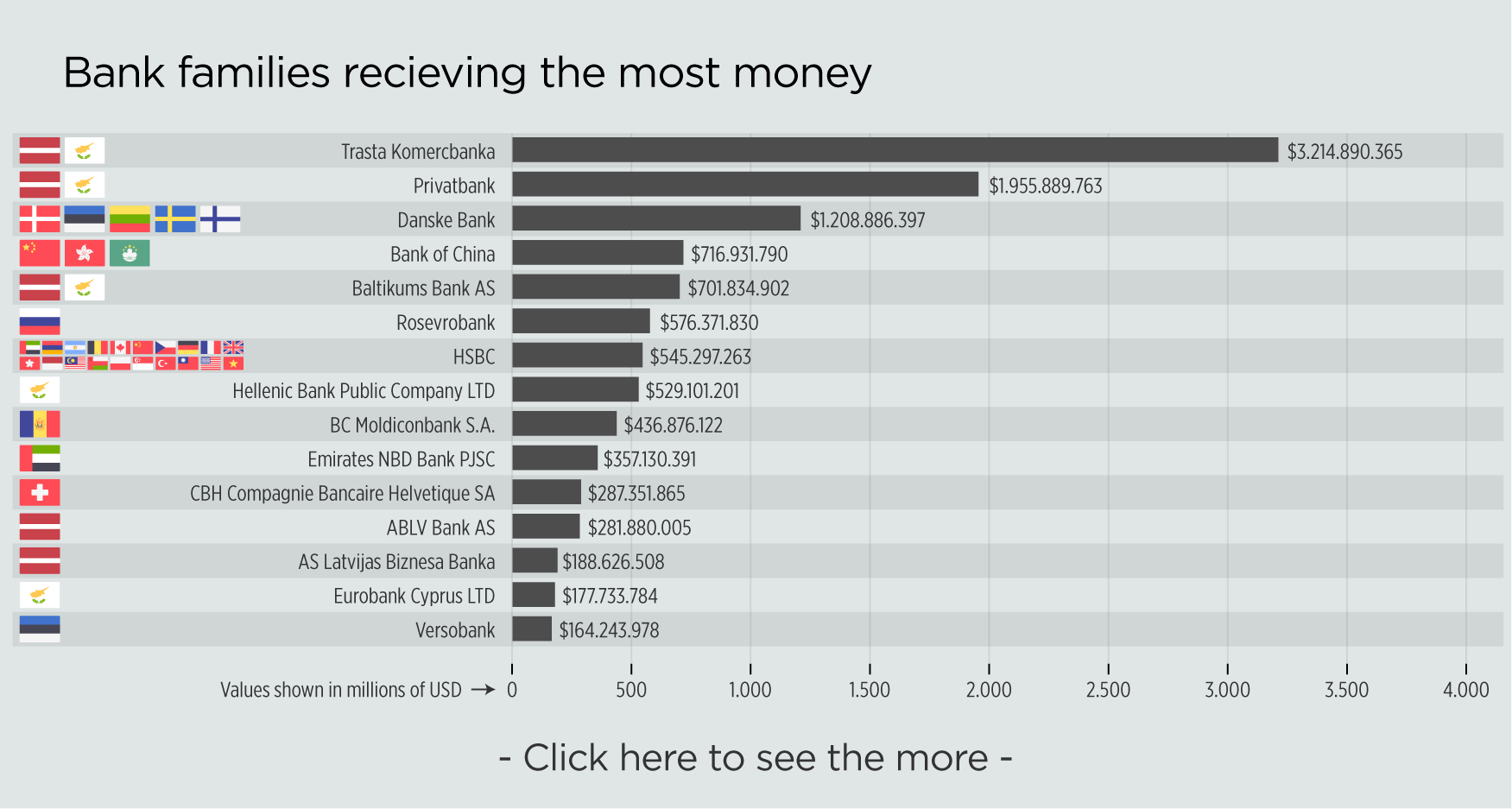

Here are the top 50 banks into which money from the scheme was deposited.

The Story Source:

Three years after the “Laundromat” was exposed as a criminal financial vehicle to move vast sums of money out of Russia, journalists now know how the complex scheme worked – including who ended up with the $20.8 billion and how, despite warnings, banks failed for years to shut it down. The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) broke the story of the Laundromat in 2014, but recently the reporters from OCCRP and Novaya Gazeta in Moscow obtained a wealth of bank records which they then opened to investigative reporters in 32 countries.

Their combined research for the first time paints a fuller picture of how billions moved from Russia, into and through the 112 bank accounts that comprised the system in eastern Europe, then into banks around the world.

Reporters can now say that much of the money ultimately found its way to Russian businessmen who own groups of companies involved in construction, engineering, information technology, and banking. All held hundreds of millions of US dollars in state contracts either with the government directly, or with state-owned entities. They are named in this project and their spending sprees on fancy autos, prep school fees, furs, and electronics are revealed.

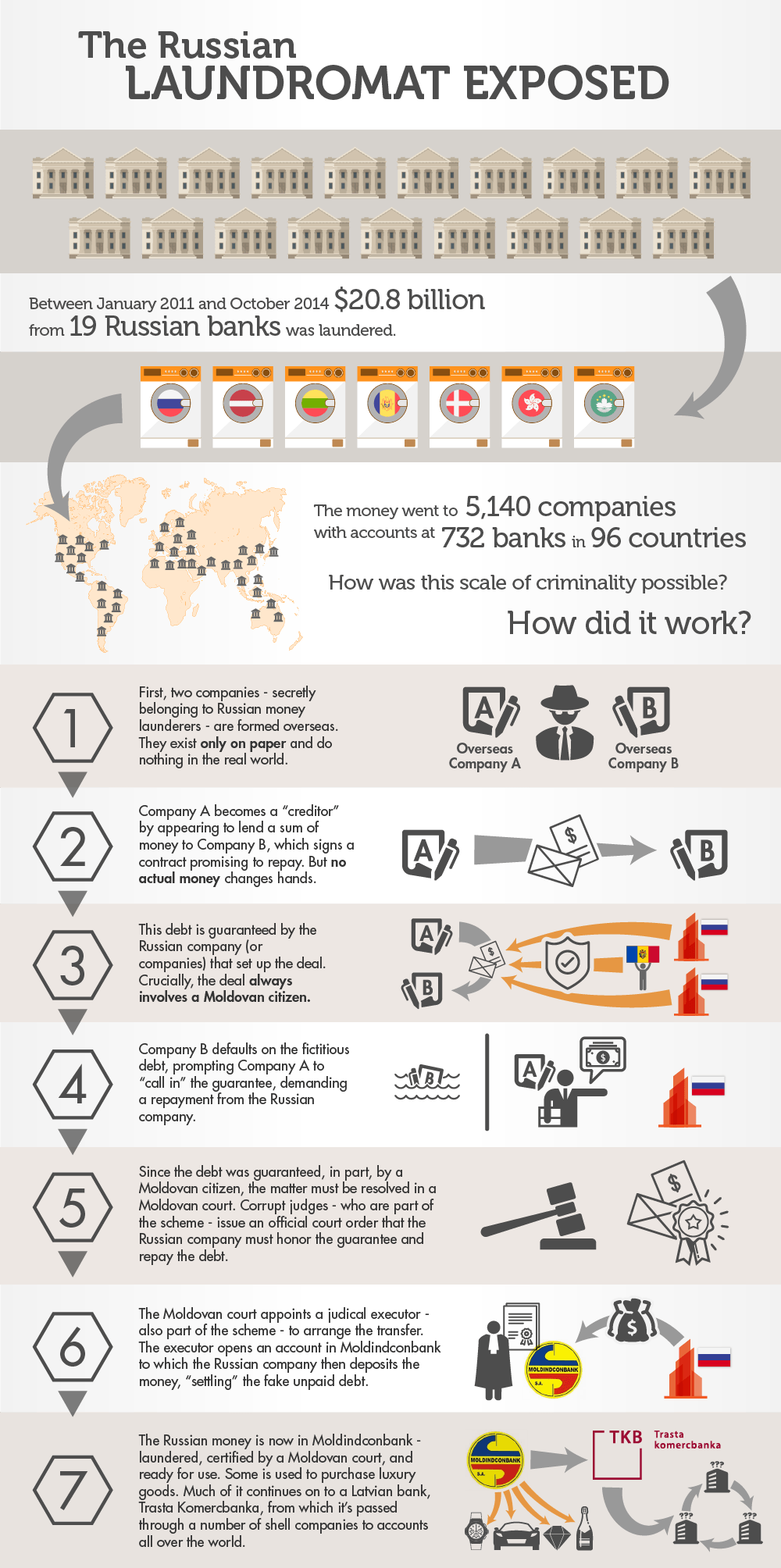

Law enforcement in Moldova, Latvia, the United Kingdom, and Russia continue to investigate the Laundromat, but attempts to bring those responsible to justice and to recover the money have been hampered in part by the reluctance of Russian officials to cooperate. Money to Play With. Money entered the Laundromat via a set of shell companies in Russia that exist only on paper and whose ownership cannot be traced. Some of the funds may have been diverted from the Russian treasury through fraud, rigging of state contracts, or customs and tax evasion. Money that might have helped repair the country’s deteriorating roads and ports, modernize the health care system, or ease the poverty of senior citizens – was instead deposited in a Moldovan bank.

At the other end of the Laundromat, money flowed out for luxuries, for rock bands touring Russia, and on a small Polish non-governmental organization that pushed Russia’s agenda in the European Union. (It is run by Mateusz Piskorski, a Polish pro-Kremlin party leader arrested for spying for Russia). Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi got paid too. The Hungarian-born, California-based psychology professor is noted for naming the psychological concept of flow – a highly focused mental state.Well-known companies unwittingly took part when beneficiaries used their Laundromat money to buy goods and services.

South Korea’s Samsung received laundered money, as did the Swedish telecom company Ericsson, and the toolmaker Black & Decker. In the United States, $500,000 went to Total Golf Construction Inc., the company that boasts of renovating a Donald Trump golf course on Canouan Island in the Grenadines. A large Japanese electronics manufacturer got €576,000 from the Laundromat in its Austrian branch on behalf of a British company run by a Russian criminal, Sergey Magin.

The Laundromat was ingenious.

Organizers created a core of 21 companies based in the United Kingdom (UK), Cyprus and New Zealand and run by hidden owners. A number of Russian companies then used these companies to move their money out of Russia.

To get the money out, the scheme’s organizers devised a clever misdirection. They created a fake debt among some of these core shell companies and then got a Moldovan judge to order the Russian company seeking to launder funds to pay that debt to a court-controlled account. Moldindconbank in Moldova held those accounts. The companies involved in the fake debt also had accounts at the same bank. Soon, Moldindconbank was deluged with cash sent in from the Russian companies. About $8 billion was then withdrawn directly from these accounts in Moldova and spent around the world.

Several examples of the promissory notes used to send the money out of Russia.

Meanwhile, nearly $13 billion more was transferred to Trasta Komercbanka in Latvia. Some of the money disappeared into the maze of these same shell company accounts. Trasta Komercbanka’s location in the European Union made the transactions less likely to be questioned by other banks. The money was now considered “clean” European money that could be spent on anything the Russians wanted. The system worked well enough to launder some $20.8 billion – which can be seen in a database showing who received the money:

Distributing the Money

Between 2011 and 2014, the 21 shell companies fired out 26,746 payments from their various Trasta Komercbanka and Moldindconbank accounts. The payments went to 96 countries, passing almost without obstacle into some of the world’s biggest banks.

All of the core-group companies appeared to be owned by proxies standing in for hidden owners. Even directors and shareholders of the companies were fake.

Some payments did go to genuine companies for real goods – but the transactions were made not by their clients, but by the 21 core companies using bogus copy-pasted paperwork which specified goods the company didn’t sell.

Some payments went to another layer of shell companies, similar to the core group making the payments from Trasta Komercbanka.

Companies that OCCRP reporters contacted denied wrongdoing. Many said this is how their Russian clients do business – adding that they now have stopped servicing those clients. Most invoked confidentiality and refused to identify their clients.

Using company records, reporters tracked the names of some clients after executives refused to give them out. They found the heavy users of the scheme were rich and powerful Russians who had made their fortunes from dealing with the Russian state.

Among them: Alexey Krapivin, a businessman in the trusted inner circle of Russian President Vladimir Putin; Georgy Gens, a Moscow businessman who owns the Lanit group, one of the major information technology (IT) distributors in Russia, for Apple, Samsung, ASUS and other computer giants; or Sergey Girdin, whose Russian Marvel group is involved in the IT business and who is an important client of the biggest Russian-owned bank.

Some Laundromat money was funneled to companies owned by Russian citizens abroad, such as Trident International Corp., owned by Pavel Semenovich Flider.

Now a naturalized US citizen, Flider was indicted in 2015 for smuggling stockpiles of US electronics components to Russian defense technology firms.

The FBI reported to the court that Flider’s “apparent sales have gone to historically well-known entities in the Russian military-industrial complex, three of which have been either directly targeted or indirectly impacted by US sanctions against Russian defense technology entities.”

The Big Banks

Finally, payments of laundered money slid easily into the world’s biggest international banks.

The Laundromat illustrates that the world’s banking system has been impotent, unable to stanch massive flows of illicit money. Bank officials offer a number of reasons as to why this is so – including that their Russian counterparts have not been helpful.

Still, HSBC, Deutsche Bank, Bank of China, Bank of America, Danske Bank, and Emirates NBD Bank all ended up with tainted money.

When OCCRP first reported on the Laundromat, Trasta Komercbanka was quick to call the story “a jumble of distorted facts and speculations of journalists against the bank.” Two years later, in the spring of 2016, Trasta Komercbanka was shut down for failure to comply with money laundering regulations.

Investigations began in three countries after the news broke, but have stalled since. Moldovan-Russian cooperation on the investigation seemed off to a good start when in September 2014, a month after OCCRP published its first Laundromat story, Russian investigators Aleksei Shmatkov and Evgenii Volotovskii arrived in Chișinău to meet their Moldovan counterparts.

They bore passports issued with consecutive numbers the day before their arrival, suggesting to the Moldovans they were dealing with secret service agents given credentials just for the meeting.

They stayed for two days and were accompanied around the Moldovan capital by a Russian embassy representative. Moldovan investigators say they got no helpful information from the two visitors – or from anyone in Moscow.

Moldovans involved who have asked to remain anonymous said they felt caught in a ping-pong game with Moscow: each time they tried to get hold of someone, they were directed to a different department of the Federal Security Service of Russia (FSB), one of the main intelligence agencies and the successor to the Soviet KGB.

Earlier this month, the Moldovan Parliament lodged an official complaint saying that the farther along Moldovan investigators got in figuring out the Laundromat, the more the Russian government “harassed” and “abused” Moldovan officials trying to enter Russia.

Viorel Morari, head of the anti-corruption prosecution office in Moldova, said they had brought criminal charges against 16 judges.

“We have 14 cases in court. Four of the judicial executors are charged. One is missing and we issued a search warrant for him, too, and two cases are already in court. Seven persons from Moldindconbank are also under investigation,” he said.

FSB representatives served on the board of at least one of banks that wired billions out of Russia as did Igor Putin, Putin’s cousin. He was a manager and executive board member in the Russian Land Bank. This bank wired more than $9.7 billion to Moldindconbank in Moldova, most of which went on to Trasta Komercbanka and from there on to the world.

WHERE DID THE MONEY GO?

INTERACTIVE MAP