Brexit Boardroom: The process of withdrawing from the European Union

The technical aspects of the withdrawal process from EU were addressed by the Lords European Union Select Committee when it held a hearing to discuss an HM Government paper on the subject. The committee, which met on May 4, reached the following conclusions.

The right to withdraw from the EU

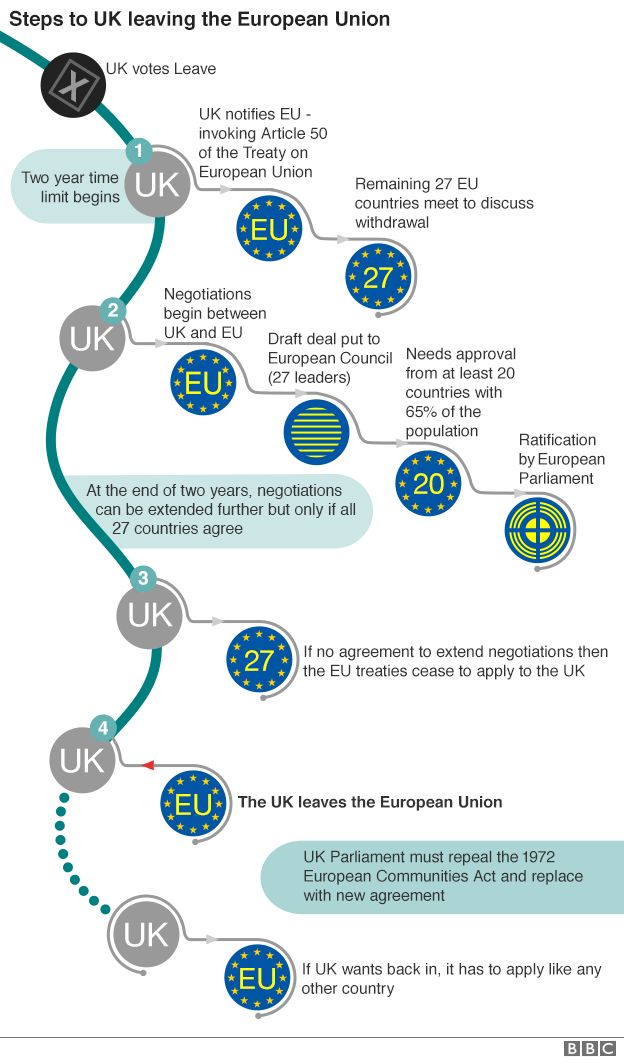

- If a member state decides to withdraw from the EU, the process described in art 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon is the only way of doing so which is consistent with EU and international law.

- There is nothing in art 50 which would formally prevent a member state from reversing its decision to withdraw during the withdrawal negotiations.

- Withdrawal from the EU is final once the withdrawal agreement enters into force.

- Article 50 makes it clear that if a state which has withdrawn from the EU seeks to rejoin, its request shall be subject to the same procedures as any other applicant state.

- The committee noted that the European Council had stated explicitly that the changes agreed in February 2016 to the terms of the UK's membership of the EU, would automatically fall in the event of a vote to leave on June 23.

- EU member states would retain significant control over the withdrawal negotiations, despite the commission having responsibility for their conduct.

- The European Parliament's right not to give its consent to the adoption of the withdrawal agreement would give it considerable influence.

- One of the most important aspects of the withdrawal negotiations would be the complex and daunting task of determining the acquired rights of the two million or so UK citizens living in other member states, and equally those of EU citizens living in the UK.

- It is likely that an agreement on the UK's future relationship with the EU would be negotiated in tandem with the withdrawal agreement.

- It would be in the interests of all parties to coordinate the negotiations closely.

- The member states would retain significant control over the negotiations on a future relationship.

- There is the potential for groups of member states to veto elements of the agreement.

- An agreement would not be deemed to have been reached until all the details had been finalised.

- The European Parliament would have the right to withhold giving consent to the adoption of the agreement on the new relationship.

- No firm prediction can be made as to how long the negotiations on withdrawal and a new relationship might take.

- Negotiations would be likely to take several years; trade deals between the EU and non-EU states have taken between four and nine years on average.

- It would be in the interests of the UK and its citizens, and in the interests of the remaining member states and their citizens, to achieve a negotiated settlement.

- This would almost certainly necessitate extending the negotiating period beyond the two years provided for in art 50.

- Although it is possible that the European Council would agree to an extension, the requirement for unanimity means that such agreement cannot be guaranteed.

- Were no extension to be agreed, the UK would be likely to have to trade on World Trade Organisation terms, placing tariffs on imports from the EU.

- The EU would place tariffs on imports from the UK.

- The acquired rights of millions of individuals and companies would remain unresolved.

- Although the UK would remain a full member of the EU during the withdrawal negotiations, its credibility as a member would be severely undermined.

- A policy of selective disengagement from some areas of EU policy might be necessary.

- The UK had been scheduled to hold the presidency of the council in the second half of 2017, but the committee noted that a vote to withdraw would disquali y the UK, by virtue of art 50, from chairing any council meetings on the withdrawal negotiations since these meetings would no doubt form a significant part of the council's activities.

- Were the electorate to vote to withdraw from the EU, the UK government should give immediate consideration to suggesting alternative arrangements for its presidency.

- Should the UK decide to withdraw from the EU, the UK parliament should have enhanced oversight of the negotiations on the withdrawal and the new relationship, beyond existing ratification procedures.

- Domestic disentanglement from EU law would require a review of the entire corpus of EU law as it applies nationally and in the devolved nations.

- Such a review would take some years to complete.

- The government of the day might well wish to maintain a significant amount of EU law in force in national law, because it would be in the national interest to do so.

- Helen Parry is a regulatory intelligence expert in the Enterprise Risk Management division of Thomson Reuters Regulatory Intelligence in London; the views expressed are her own