The Post-Soviet States Money-Laundering Case Studies

The UK government’s recent National Risk Assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (NRA) and subsequent Action Plan identified the need to fill intelligence gaps in relation to high-end money laundering in the UK. In particular it seeks a better understanding of the role of the financial and professional services sectors, such as banks, lawyers, accountants, and trust and company service providers (TCSPs), in laundering proceeds of crime.

There are numerous case studies of how money has been laundered through the UK, a systematic examination of which would begin to fill some of the current gaps. Two schemes originating in post-Soviet jurisdictions help to identify certain risks. The UK is often only one part of the broader intelligence picture that should be analysed more fully to understand the real money-laundering risks.

THE RUSSIAN LANDROMAT

The first case study concerns what has been dubbed the ‘Russian Laundromat’. It involved two UK-registered companies signing a bogus contract, with one company lending a fictitious amount of money to the other. When the borrower purported to refuse to repay the debt, the guarantors of the loan, based in Russia, took the case to Moldovan courts. A corrupt and complicit judge then certified the fake debt as enforceable, and money was transferred from the Russian guarantors to the ‘lending’ company’s account which, as in many such cases, was situated in Latvia.

A problem facing the UK’s regulatory environment, therefore, is the absence of checks to verify the veracity of business activity conducted by UK-registered companies. Companies House, responsible for incorporating and dissolving companies in the UK, is, however, not responsible for verifying the accuracy of information submitted by companies that are registering. This represents a potential vulnerability that can be abused, given the ease with which companies can be registered in the UK. This presents a challenge, as the UK will not wish to undermine this ease of doing business in the UK, particularly in post-Brexit economic uncertainty. However, it is a theme that needs further consideration within the NCA and possibly the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, which oversees Companies House, since fictitious business activity between two UK-registered companies has featured in many money-laundering schemes.

THE $1 BILLION THEFT

The $1 billion theft from a group of Moldovan banks in 2015 highlighted a key risk surrounding UK-based trust and company service providers. TCSPs are often crucial enablers to money laundering, which the Action Plan recognises as part of the intelligence gap that must be filled. A report by investigative consultancy firm Kroll claimed to have uncovered a group of UK companies, many, again, with Latvian bank accounts, which were allegedly used to funnel the stolen money offshore. One of the key companies allegedly with a title to the missing £1 billion was formed by an Edinburgh-based formation agent, and registered in the UK as a limited partnership of two Seychelles-registered companies.

This case highlights vulnerabilities in due diligence requirements. The UK’s Money Laundering Regulations, which should be updated in line with the European Union’s Fourth Money Laundering Directive, requires regulated companies to take risk-based customer due diligence measures to gain comfort that the business is not involved in illicit activity. In a BBC interview with an individual running the Edinburgh-based formation agent responsible for the set-up of the Seychelles-owned limited company, - it subsequently emerged that the Seychelles-owned limited partnership’s beneficial owners were known to the formation agent, but questions were, allegedly, not asked about the nature of the business, as required by customer due diligence measures when establishing a commercial relationship.

The individual said that asking such questions was the role of the Latvian-based intermediary agent with whom they worked. The UK Money Laundering Regulations do allow for ‘reliance’ on another relevant person to conduct due diligence on their behalf in other EEA states; there are narrow professional requirements as to what kind of individual or company can take on this role, and it is unclear whether the intermediary met these requirements. An added risk is that there are many companies in Latvia working as ‘business introducers’, which assist clients (usually from former Soviet states) in setting up shell firms and bank accounts for clients abroad.

LATVIAN BANKS FUEL SCOTLAND SHELL COMPANIES

The trail of company service providers in Scotland that have churned out thousands of shell companies over the last few years leads to the top echelons of Latvian banks, according to bne IntelliNewsenquiries.

A cluster of interlinked Edinburgh corporate service providers have been churning out Scottish shell companies by the thousands over the last few years, constituting a veritable ‘factory’ of companies that do not actually do any business or have any assets.

A report by US corporate investigators Kroll into how $1bn was stolen from Moldovan banks have pinpointed these Scottish shell companies as having played the role of getaway cars for the money looted from the Moldovan banks. According to the report, a total of 28 firms registered in Scotland, along with 20 from elsewhere in the UK, were involved in the heist. But with Scottish shell firms being such a rare phenomenon until recently, tracing their creators is proving more straightforward than usual.

Enquiries by bne IntelliNews sources in Edinburgh suggest that the bulk of Scottish shell companies relate to a handful of addresses – and these can again be traced mostly to two company service providers, Royston Business Consultancy and Arran Business Services, registered at the same Edinburgh address, together with a third Edinburgh outfit that shared personnel with Royston and Arran, and other feeder structures at around a dozen different addresses, mostly linked by personal or corporate ties.

As bne IntelliNews has reported, these addresses have not just churned out firms for the Moldovan bank heist, but also for two previous massive money-laundering schemes that have wracked Moldova – one of them seeing a staggering €20bn moved from Russia via Moldova to Latvia during 2010-2014.

The proliferation of Scottish limited partnerships (LP) – which date back to the Limited Partnerships Act of 1907 and under the law are not required to disclose their annual accounts or even the names of the people who control them – is also visible in other Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, although they have not yet triggered scandals on the scale of the recent Moldovan disaster. Anger over the looting of the three banks – Banca Sociala, Banca de Economii and Unibank – to the tune of almost MDL1.8bn (€897mn), more than 10% of Moldova’s GDP, has brought thousands of Moldovans out on to the streets to protest against the government since it was uncovered in November 2014.

For instance, Ukraine’s company register shows up more than 100 Ukrainian firms owned wholly or partly by Scottish LPs, almost all of them since 2010, many of them with the same handful of addresses as featured in the Moldovan scandal.

According to an investigation by Scotland’s Sunday Herald, as many as 11,000 shell companies may have been created in Scotland in recent years, with current production running at about 300 per month – the bulk of which can be accounted for by the same dozen addresses.

But for readers of bne IntelliNews, there is nothing new in the mass creation of UK shell companies, partly for use in money laundering in the CEE region. And in this case as well, the original driver behind the mass creation of shell companies appears to come from the same place: Latvia’s controversial offshore banking sector, which played a key role in the Moldovan heist, according to the Kroll report. “Shareholders financed their acquisition [of Moldovan banks] with funds borrowed from UK Limited Partnerships who have accounts at Latvian banks... Subsequent to the change in ownership, [$1bn] loan receipts [from the Moldovan banks] were passed to Latvian bank accounts in the name of UK Limited Partnerships,” the Kroll report reads.

Laundered in Latvia

The $1bn Moldovan bank fraud is only the latest in a series of monster money-laundering scandals that have been linked to the offshore Latvian banks. But the scandal usually explodes in the country of origin of the stolen money, with barely a murmur in Latvia itself.

While Latvia’s domestic banking is largely in the hands of respectable Scandinavian banks, it hosts a segregated dollar-denominated offshore banking sector that caters to clients from Russia and other former Soviet states of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The welcome mat for Russian money stands in stark contrast to the Baltic state's strident political posturing against Russian aggression in Ukraine and elsewhere in the post-Soviet space.

It is widely accepted that the basic operation performed by Latvia’s offshore banks is to move funds out of the post-Soviet countries into the international financial system, often ultimately landing in Swiss bank accounts or elsewhere in the West. Latvian regulators refer to this business model as “financial logistics” and justify it by saying that Latvia strictly complies with all state-of-the-art anti-money laundering requirements.

CIS clients of Latvia’s offshore banks are usually incorporated as shell companies registered in Western countries or tax havens, which explains why the business generates mass demand for UK shell companies.

According to unpublished figures from Latvian regulators Financial and Capital Market Commission (FCMC) seen by bne IntelliNews for 2011, 13.7% of depositors in Latvia’s offshore banks were incorporated as UK firms, another 23.3% were incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, 7% in Cyprus, and the rest in a whole spectrum range of tax havens across the world, compared with a mere 6% actually incorporated in Russia.

Introducing the introducers

As bne IntelliNews has frequently described, a shadowy but key role in the Latvian bank model is played by so-called ‘business introducers’ – structures that not only set up shell firms for bank clients, but also handle the process of opening the bank accounts for these clients.

Leading Latvian offshore banks openly seek relationships with new ‘business introducers’ on theirwebsites. Such business introducers handle customer identification both for the shell firms and the bank accounts – a role that is at the heart of anti-money laundering laws. Critics argue that the arrangement creates a layer of deniability between the bank and clients, and thus massively dilutes anti-money laundering regulations.

According to bne IntelliNews enquiries, such business introducers are themselves usually shadowy structures, registered in offshore jurisdictions, with hidden ownership, shifting management configurations, and often personal ties to banks. All this makes them unlikely fighters of money laundering.

Latvian regulators reject the criticism. “It is the legal duty of banks to carry out customer due diligence based on risk assessment to every client, including business introducers,” Latvia’s Financial and Capital Market Commission told bne IntelliNews, adding contrary to the evidence, “the use of such intermediaries is not widespread among banks in Latvia".

Strange Arran-gements

In the case of the Scottish offshores, the trail to Latvia’s banks is particularly easy to trace: the Edinburgh company service provider Arran Business Services, part of the cluster of addresses churning out Scottish shell companies, is an affiliate of Arran Consult, a ‘business introducer’ operating across CIS countries. And the Arran Consult Russian-language website advertises its partnership with leading Latvian banks, among others, with its services encompassing setting up shell firms in multiple jurisdictions and opening bank accounts for those shell firms.

The Latvian banks listed as partners include three of Latvia’s largest offshore banks – ABLV, Rietumu and Norvikbanka. Notably, 14 of the shell companies listed in the Kroll report had business relationships with ABLV, formerly known as Aizkraules, which describes itself as providing “the most highly valued private banking experience, based on a unique understanding of our clients".

Arran Business Services is owned by a Panamanian offshore company with untraceable ownership. But its manager since 2011 is a Latvian, Vitalijs Savlovs, who is also owner and director of a UK firm called Arran Consult, while in Latvia he is owner of Riga firm Arran Latvia.

Savlovs’ services for Latvian banks appear to go beyond doing mere paperwork for bank clients to a more hands-on role in their business, as well as close personal ties to the banks themselves.

In 2014, a London High Court decision cited Arran Business Services and Savlovs as incorporating companies used as ‘getaway vehicles’ in an enormous $175mn fraud committed in 2010-2011 against Russia’s Otkritie investment bank by its own traders.

Otkritie brought the lawsuit against its former employees, among them a certain Ruslan Pinaev. The court case established that Savlovs – transliterated in the court decision from the Russian version of the name as Vitaly Shavlov – had set up one of the shell firms used by Pinaev for shifting the loot, and introduced him to a second. Savlovs himself was not accused of any wrongdoing in the Otkritie lawsuit.

According to the court decision, Savlovs was a “trusted acquaintance” of fraudster Pinaev. Notably, Pinaev was married to a Latvian banker, his co-defendant, Marija Kovarska, a former deputy vice president of Latvia’s Parex – the bank which had pioneered offshore banking model in Latvia from 1991 until its collapse in December 2008.

The Otkritie cases provides yet another example of how Latvia’s offshore banks are used to move dirty money westwards. The clients of three different Latvian banks were involved in laundering the $175mn funds stolen from Otkritie. The firms that Savlovs organised for Pinaev, according to the court decision, both had accounts at Latvia’s Baltikums Bank, “an international private bank that provides a wide range of financial and advisory services, including tailor-made solutions for high net worth individuals and businesses,” according to its website.

bne IntelliNews found further pointers to Savlovs’ close connections to the upper echelons of Latvian offshore banking, and Baltikums Bank in particular in 2010-2012. Such connections underscore that the shadowy ‘business introducer’ structures partnering the banks may be personally linked to the banks.

According to Latvian company records, Savlovs had a seat on the board of one Latvian affiliate of Baltikums Bank, BB Trust Consultancy, until 2012. “BB Trust Consultancy Ltd was not Baltikums Bank’s subsidiary in legal terms,” Baltikums Bank told bne IntelliNews.

Savlovs may also have organised at least one Scottish company directly for Baltikums Bank: Edinburgh-registered CityCap Development LP, set up by Arran Business Services, owns a historical Riga office building, reportedly on behalf of Baltikums Bank. The bank has a subsidiary called Citycap Service, and registered another subsidiary in the building.

Notably, a 2010 version of the Arran Consult website lists as a Skype name for contacts simply ‘Baltikums’. “Skype contact Baltikums is not related to Baltikums Bank in any way,” the bank claimed tobne IntelliNews.

Baltikums Bank was not one of the banks mentioned in the Kroll report as having clients who transited funds stolen from Moldova, and is also not a bank featured on the Arran Consult website as a partner. The bank denied having any current business relationship with Savlovs or his Arran companies.

According to the Otkritie court case, Savlovs was based in Scotland already in 2010, roughly the same time as when the mass production of Scottish shell companies started. Savlovs became director of Arran Business Services in 2011.

Savlovs failed to respond to emails to his London office where he is currently based. His wife and business partner Aleksandra Savlova also failed to respond. A woman with the same (unusual) name as Aleksandra Savlova is listed as having been a manager at leading Latvian bank ABLV in 2006-2008.

bne IntelliNews spoke with Dmitry Sokolov, head of Arran Consult’s office in St Petersburg, Russia. Sokolov acknowledged that Arran Consult specialises in supplying Scottish companies to Russian clients of Latvian banks, praising Scottish firms for easy administration, low costs and prestigious jurisdiction. He also acknowledged that the business has its representatives in Scotland who incorporate the firms. But he denied any current connection to Savlovs. “We have broken off our partnership with Vitalijs because of poor quality of service,” he said. “Arran Consult in Russia is no longer connected to Vitalijs, and we have no connection to the Moldovan case.”

This case raises doubts over the adequacy of the sector’s regulatory and enforcement oversight of whether companies are conducting due diligence effectively or whether they are simply meeting regulatory requirements. HM Revenue and Customs is the UK’s main supervisor of TCSPs, although the supervisory regime is fragmented across other organisations, such as the Financial Conduct Authority and professional bodies, depending on the activity of the TCSP. TCSP supervisors conduct desk-based reviews and compliance visits, but, given that the NRA identified the role of TCSPs in money laundering as part of the intelligence gap, it is difficult to know whether supervisors can be confident that they understand the risks about them well enough to be as effective as possible. Supervisors and law enforcement could, for example, draw on the successes of the Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce (JMLIT), which has been helpful in public–private financial sector intelligence sharing and confidence building.

Numerous other ex-Soviet state cases provide useful focus points for filling the intelligence gap, such as the Russian fraud highlighted by the late lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, whichinvolved UK-based companies systematically wiring embezzled money offshore, or a Surrey-based mansion owned through an anonymous company linked to a Kyrgyzstan-based money-laundering scheme.

1) RUSSIAN RECORDS

Banking records obtained by OCCRP show that cellist Sergei Roldugin, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s old friend, received money from an offshore company at about the same time it was being used to steal money from the Russian government in the notorious Sergei Magnitsky case.

The Magnitsky case involved the theft of US$ 230 million from the Russian Treasury and is one of the largest tax fraud cases in Putin’s Russia. The crime was uncovered in 2007 by Magnitsky, a Russian lawyer who was working for Hermitage Capital Management, then the biggest foreign investor in Russia.

Magnitsky was arrested by the same police officers whom he accused of covering up the fraud. He was thrown into jail, where he died of mistreatment and inadequate medical care. Despite his death, the government of Russia continued to prosecute him.

The Rosneft Shares

A commercial contract from May of 2008, obtained by OCCRP from the Panama Papers, indicates that International Media Overseas SA (IMO), a Panama company which at the time was solely owned by Roldugin, sold 70,000 shares of Rosneft, a large state company, for a bit more than US$ 800,000 to a British Virgin Islands (BVI) corporation, Delco Networks SA (Delco).

The shares were paid for with money transferred from Delco’s bank account in the Lithuanian bank UKIO Bankas to Roldugin’s IMO bank account in the Zurich branch of Gazprombank (Switzerland) formerly known as the Russian Commercial Bank (Zurich).

The contract was buried in the Panama Papers, a trove of internal data of Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian legal firm doing business in offshore tax havens for clients who want to hide their identities and/or holdings.

The data was obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists with OCCRP and more than 100 media partners from 76 countries.

Delco and its associated companies were likely part of a large offshore money laundering network, dubbed the Proxy Platform, set up by organized crime and involving companies and bank accounts in Russia, Moldova, the United Kingdom (UK), Latvia and offshore tax havens that was used by the Russian government and numerous crime gangs to steal or launder money, evade taxes and pay bribes.

The Magnitsky Case Network

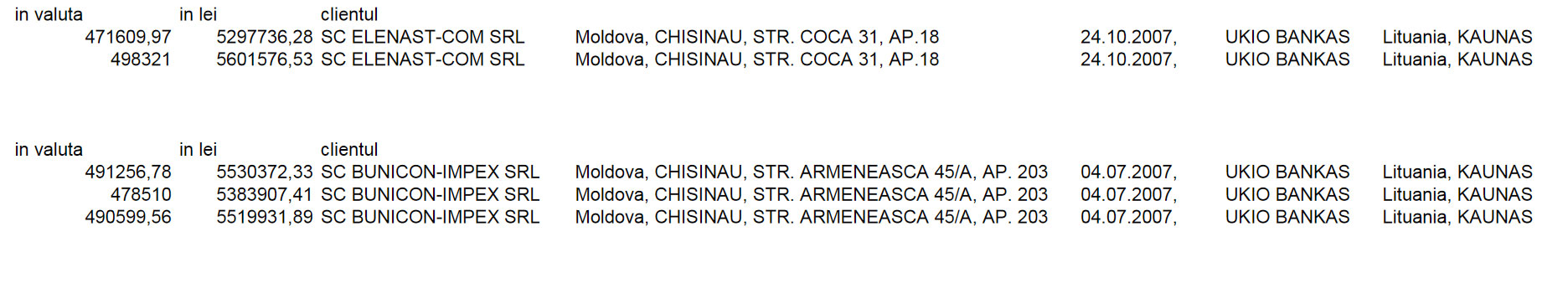

After the money was fraudulently taken from the Russian treasury, it disappeared into a series of paper companies in early 2008. Two of those companies were the Moldovan-registered Elenast-Com SRL, located in a Communist-era block of flats, and Bunicon-Impex SRL, which claimed headquarters in an abandoned building in Chisinau.

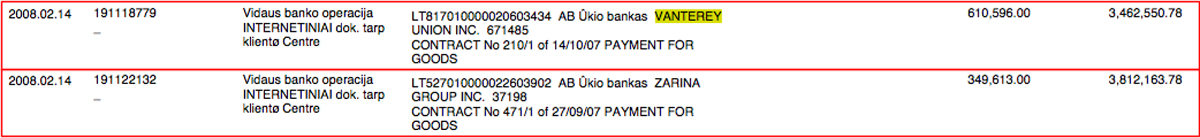

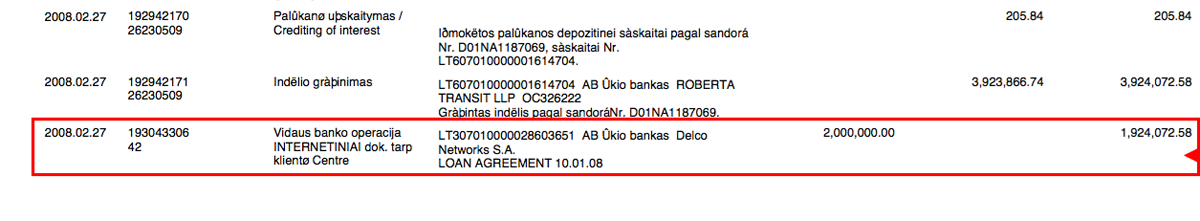

Elenast and Bunicon sent a share of the stolen money in February 2008 to a BVI company, Vanterey Union Inc., which then wired funds to Roberta Transit LLP, a UK- based company. Roberta Transit, in turn, sent that money along with money from other related companies (US$ 2 million in all) to Delco. The payments flowed in quick succession, all of them reaching Delco in the same month.

Besides Vanterey, three other companies used in the Magnitsky case–Protectron Company Inc., Wagnest Ltd., and Zarina Group Inc.–also sent funds to Roberta Transit. Like Vanterey, Zarina Group also received money from the two Moldovan paper companies in February 2008.

Two months later, Delco purchased the Rosneft shares from Roldugin, sending the cellist’s company US$ 800,000 in May, 2008.

Roberta Transit, which was dissolved in 2009, was set up as an opaque limited liability partnership between two BVI-registered companies: Milltown Corporate Services and Ireland & Overseas Acquisitions Ltd. These two BVI companies played a role in frauds in the arms trade, pharmaceuticals and other businesses.

The two Moldovan companies, Elenast and Bunicon, were also involved in a number of other Magnitsky related transfers. Money that went through their accounts ended up invested in luxury apartments in the heart of the Wall Street area of New York City. Those apartments are currently under a seizure order by the US government.

The Moldovan companies also had bank accounts in Banca de Economii a Moldovei, a bank which was shut down in 2015 after being used in one of the biggest frauds in Moldova’s history – the theft of US$ 1 billion from three banks.

Vanterey, Roberta and Delco used bank accounts at the Lithuanian-based UKIO Bankas, which was also shut down in early 2013. Lithuanian banking authorities closed the bank due to its poor financial standing in early 2013. Its main shareholder, Vladimir Romanov, fled the country. Suspected of widespread embezzlement, Romanov was granted asylum in Russia in 2014.

Roldugin has told Russian media that the money was donations from Russian businessmen which he used to purchase expensive musical instruments. Russian officials, however, seemed to acknowledge that the state had in fact knowingly used the criminal networks, including possibly Roldugin’s offshores.

Earlier this month on Vesti Nedeli, a Russian television program, in an interview with Roldugin, the program revealed a claim allegedly by officials in the Russian government that the network of offshores might have been used to foil a 2008 plot by the CIA to buy Russia’s cable television network.

According to a Moscow Times report on the program, “Russia’s security services asked Russian companies and banks to transfer US$ 1.5 billion offshore to ward off the US threat and keep the assets in local hands. Though not stated outright, the program implied that Roldugin’s companies had been used.”

OCCRP could not independently verify the claims and Roldugin could not be reached for comment.

Magnitsky’s employer, Bill Browder of Hermitage Capital, sees a simpler explanation telling OCCRP: “We’ve always wondered why Putin would be ready to ruin his relations with the West to support and protect the criminals in the Magnitsky case. This new information explains a lot.”

By analysing such case studies, a fuller picture of where the UK fits into these schemes begins to form. Money-laundering ‘red flags’ can be more specifically identified and better prioritised by sector or business activity. Better questions can be asked as to why a company is structured or transacts in the way it does. It will also help to identify which jurisdictions the relevant supervisors and law enforcement could connect with more to build a fuller intelligence picture, with Latvia a good example. Without this, a ‘risk-based approach’ will continue to go only as far as the integrity and interpretation of the company in question.